Persistent Versioning

In this post, I’d like to introduce a version scheme that I call Persistent Versioning. Most of the ideas presented in this post are not new or my own. Let me know if there’s already a name for it.

In 2015, Jake Wharton (@JakeWharton) wrote a blog post titled Java Interoperability Policy for Major Version Updates:

A new policy from @jessewilson and I for the libraries we work on to ensure major version updates are interoperable: https://t.co/zKqYRwrXmq

— Jake Wharton (@JakeWharton) December 11, 2015

Rename the Java package to include the version number.

This immediately solves the API compatibility problem from transitive dependencies on multiple versions. Classes from each can be loaded on the same classpath without interacting negatively. ….

(Libraries with a major version of 0 or 1 can skip this, and only start with major version 2 and above.)

Include the library name as part the group ID in the Maven coordinates.

Even for projects that have only a single artifact, including the project name in the group ID allows future updates that may introduce additional artifacts to not pollute the root namespace. In projects that have multiple artifacts from inception, it provides a means of grouping them together on artifact hosts like Maven central. ….

Rename the group ID in the Maven coordinates to include the version number.

Individual group IDs prevent dependency resolution semantics to upgrade older versions to newer, incompatible ones. Each major version is resolved independently allowing transitive dependencies to be upgraded compatibly. ….

(Libraries with a major version of 0 or 1 can skip this, and only start with major version 2 and above.)

In the tweet thread Jake cites RxJava’s two GitHub issues Version 2.x Maven Central Identification ReactiveX/RxJava#3170 and 2.0 Package Name ReactiveX/RxJava#3173, both opened by Ben Christensen (@benjchristensen).

RxJava

RxJava 2.x was released under different organization (group ID) and package name:

Maven address and base package

To allow having RxJava 1.x and RxJava 2.x side-by-side, RxJava 2.x is under the maven coordinates

io.reactivex.rxjava2:rxjava:2.x.yand classes are accessible belowio.reactivex.Users switching from 1.x to 2.x have to re-organize their imports, but carefully.

As noted in the GitHub issues and also in the quote above, this was done consciously so both 1.x and 2.x can co-exist side-by-side.

Square Retrofit and Square OkHttp

In Java Interoperability Policy for Major Version Updates Jake announced that Square Retrofit 3.x and Square OkHttp 2.x will adopt the policy.

Major version updates to libraries solve the API warts of old and bring shiny new APIs to address previous shortcomings—often in a breaking fashion. Updating an Android or Java app is usually a day or two affair before you reap the benefits. Problems arise, however, when other libraries you depend on have transitive dependencies on older versions of the updated library.

Jake mentions the difficulty of the problems introduced by transitive dependencies, sometimes described as the diamond dependency problem.

Apache Commons Lang

Back in 2011 Apache Commons team announced Apache Commons Lang 3.0.

… We’ve removed the deprecated parts of the API and have also removed some features that were deemed weak or unnecessary. All of this means that Lang 3.0 is not backwards compatible.

To that end we have changed the package name, allowing Lang 3.0 to sit side-by-side with your previous version of Lang without any bad side effects. The new package name is the exciting and original

org.apache.commons.lang3. This also forces you to recompile your code, making sure the compiler can let you know if a backwards incompatibility affects you.

This might be one of the earlier well-known examples where both the package name and the group ID (organization name) were changed for the explict purpose of allowing two versions of the same library to coexist in a single classpath.

do not become addicted to versions

Full discosure: As a day job, I maintain sbt, a build tool for Scala and Java projects that also acts as a package manager using Apache Ivy and the Maven ecosystem. That doesn’t mean my opinions qualify for anything, but just an indication that I think about this topic from time to time.

In an early scene from Mad Max: Fury Road, Immortan Joe showers water on to the ragged citizens of the post-apocalyptic desert for a minute, stops it, and declares: Do not, my friends, become addicted to water. It will take hold of you, and you will resent its absence. If I may paraphrase this in our context:

Do not become addicted to versions. They will take hold of you, and you will resent their absence.

Basically, my feeling about the version number is that it’s something we need to rely less on. First of all, it’s a String. As a programmer of an application, you have little control of what the strings would end up as, as they are selected by dependency resolvers like Maven and Ivy. The situation for library authors are even worse, since they have no control over who might use their code with what transitive dependencies.

As String, the version numbers in on itself do not have sorting order or meanings. Here, again, we must concede to the implementation details of Maven and Ivy, such as ComparableVersion that gives special meaning to “beta or b”.

As programmers of Scala, Java, and other statically typed languages we pride ourselves in being able to avoid many of the erroneous behaviors at compile time, and we even think about laws and global uniqueness (coherence) of typeclasses. We spend so much time and energy when we code, but when we deploy the services to the production the JAR files are arbitrarily selected by the dependency resolvers. As long as we accept Maven and Ivy, Liskov is a lie.

For example, when more than one versions are found in the dependency graph, Ivy uses latest-wins for Ivy artifacts, Maven uses nearest-wins, and Ivy emulates the nearest-wins for Maven artifacts. This means, that at the whim of the application developer, your library’s dependency can get upgraded or downgraded to some other version.

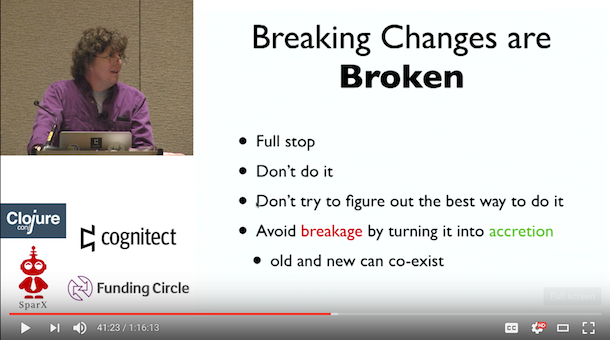

Spec-ulation Keynote

In December 2016, Rich Hickey gave an interesting keynote for Clojure/conj on this topic called Spec-ulaiton Keynote (Thanks Alexandru for the pointer).

Breaking changes are broken. It’s a terrible idea. Don’t do it. Don’t try to figure out the right way to do it.

In this talk Rich argues for “accrual” as the mode of software changes, and never making the breaking change within the same package name.

lies, damned lies, and version semantics

One of the points Rich made in his talk, and I agree is that dependency resolvers are not at fault. They are doing the best they can to solve what amounts to over-specified constraint satisfaction problems. As per usual, the culprit is us humans.

We started overloading our hopes and meanings into these digits of numbers. The proponent of Semantic Versioning uses the first segment to denote breaking changes:

Major version X (X.y.z | X > 0) MUST be incremented if any backwards incompatible changes are introduced to the public API. It MAY include minor and patch level changes. Patch and minor version MUST be reset to 0 when major version is incremented.

The Scala compiler and the standard library adopt a variation of the Semantic Versioning where the first segment encodes a mystical “epoch” number, or the semantics of the language itself. This tradition somehow spread to the rest of the ecosystem in Scala, so many of the Scala libraries use “epoch.major.minor” scheme, where the second segment denote the breaking change.

Note that none of the semantics, neither Semantic Versioning nor Scala’s island evolutionary second-segment variation, is formalized in terms of the rules in pom.xml or ivy.xml file. They are just social conventions, sometimes documented in the websites or release notes.

ways out

One way to solve all this is to remove the notion of JAR file swapping, and compile the entire library ecosystem from source, for all commits. That is sort of what monorepo gets you, plus good caching. This is what Google does, and it comes with interesting pros and cons on its own, like everyone in the company working on one source tree.

There’s also been ideas of storing the metadata in DVCS like Git. I am somewhat skeptical of any effort that requires continuous effort to compete with Maven or Maven Central.

Persistent Versioning is a viable way out of this mess, I think, because instead of fighting the exising Maven ecosystem, it embraces it.

persistent library

If we think about this, JAR files are nothing but bags of functions. The idea of renaming package name and the organization (group ID) on breaking changes is essentially treating the JAR files as immutable collections. We can think of the resulting library as being persistent, because the datatypes and functions available in these libraries will be available permanently.

In terms of the maintenance overhead, it should not be any different from maintaining a library under Semantic Versioning where you would have to avoid binary compatibility breakages during the minor releases.

who should adopt Persistent Versioning?

If we look at the early adopters of Persistent Versioning, it should be clear that these are libraries that are intended to be used widely, and often from some other libraries as transitive dependencies. Square OkHttp, for example, is shipped as part of Android. Unless it’s impossible to have multiple versions of the library side-by-side, you should consider adopting this scheme.

prior works: Linux package names

On Linux distributions, it’s common to append major versions number when it is desired to install libraries side-by-side. Here’s parallel guide from 2002 by Havoc Pennington (then Red Hat), who I had the pleasure to work with for some time in Typesafe. It’s entirely possible that he has incepted some of these ideas back then:

The solution to the problem is essentially to rename Foo, and in most cases the nicest way to do so is to include the version number in the name of every file. This means both versions of Foo can be installed at the same time.