sbt server reboot

This is a continuation from the sbt 1.0 roadmap that I wrote recently. In this post, I’m going to introduce a new implementation of sbt server. Please post on sbt-dev mailing list for feedback.

The motivation for sbt server is better IDE integration.

A build is a giant, mutable, shared, state, device. It’s called disk! The build works with disk. You cannot get away from disk.

– Josh Suereth in The road to sbt 1.0 is paved with server

The disk on your machine is fundamentally a stateful thing, and sbt can execute the tasks in parallel only because it has the full control of the effects. Any time you are running both sbt and an IDE, or you’re running multiple instances of sbt against the same build, sbt cannot guarantee the state of the build.

The original concept of sbt server was proposed in 2013. Around the same time sbt-remote-control project was also started as the implementation of the idea. At some point, sbt 0.13 stabilized and Activator became the driver of sbt-remote-control, adding to it more constraints such as not changing sbt itself, and supporting JavaScript as the client.

With sbt 1.0 in mind, I have rebooted the sbt server effort. Instead of building something outside of sbt, I want to underengineer the whole thing. This means throwing out previously made assumptions that I think are non-essential such as automatic discovery and automatic serialization. Instead I want to make something small that we can comfortably merge into sbt/sbt codebase. Lightbend holds Engineering Meeting a few times a year where we all fly to a location and have discussions face to face, and also do an internal “hackathon.” During the Februay code retreat in beautiful Budapest, Johan Andrén (@apnylle), Toni Cunei, and Martin Duhem joined my proposal to work on the sbt server reboot. The goal was to make a button on IntelliJ IDEA that can trigger a build in sbt.

inside the sbt shell

Before we talk about the server, I want to take a quick detour. When I think of sbt, I mostly think of it in terms of task dependency graph and its parallel-processing engine.

There’s actually a sequential loop above that layer, that processes a command stored in State as a Seq[String] and calls itself again with the new State. An interesting thing to note is that the new State object may contain additional commands than what it started with, and it could even block on an IO device that waits for a new command. That is how the sbt shell works, and the IO device that it blocks on is me, the human.

The sbt shell is a command in sbt called shell. It’s short enough implementation, and it’s helpful to read it:

def shell = Command.command(Shell, Help.more(Shell, ShellDetailed)) { s =>

val history = (s get historyPath) getOrElse Some(new File(s.baseDir, ".history"))

val prompt = (s get shellPrompt) match { case Some(pf) => pf(s); case None => "> " }

val reader = new FullReader(history, s.combinedParser)

val line = reader.readLine(prompt)

line match {

case Some(line) =>

val newState = s.copy(onFailure = Some(Shell),

remainingCommands = line +: Shell +: s.remainingCommands).setInteractive(true)

if (line.trim.isEmpty) newState else newState.clearGlobalLog

case None => s.setInteractive(false)

}

}

The key is this line right here:

val newState = s.copy(onFailure = Some(Shell),

remainingCommands = line +: Shell +: s.remainingCommands).

It prepends the command it just asked from the human and shell command onto the remainingCommands and returns the new state back to the command engine. Here’s an example scenerio to illustrate what’s going on.

- sbt starts. A gnome prepends

shellcommand to theremainingCommandssequence. - The main loop takes the first command from

remainingCommands. - Command engine processes

shellcommand. It waits for the human to type something in. - I type in

"compile".shellcommand turnsremainingCommandtoSeq("compile", "shell"). - The main loop takes the first command from

remainingCommands. - Command engine processes whatever “compile” means. (it could mean multiple

compile in Compiletasks aggregated across all subprojects). TheremainingCommandsequence becomesSeq(shell"). - Go to step 2.

multiplexing on a queue

To support inputs from multiple IO devices (the human and network), we need to block on a queue instead of JLine. To mediate these devices, we will create a concept called CommandExchange.

private[sbt] final class CommandExchange {

def subscribe(c: CommandChannel): Unit = ....

@tailrec def blockUntilNextExec: Exec = ....

....

}

To represent the devices, we will create another concept called CommandChannel. A command channel is a duplex message bus that can issue command executions and receive events in return.

what events?

To design CommandChannel, we need to step back and observe how we interact with the sbt shell currently. When you type in something "compile", happens next is that the compile task will print out warnings and error messages on the terminal window, and finish either with [success] or [error]. The return value of the compile task is not useful to the build user. As a side effect, the task also happen to produce some *.class files on the filesystem.

The same can be said of assembly task or test task. When you run the tests, the results are printed on the terminal window.

The messages that are displayed on the terminal contain the useful information for IDEs such as compilation errors and test results. Again, it’s important to remember that these events are completely different thing from the return type of the task – test’s return type is Unit.

For now, we’ll have only one event called CommandStatus, which tells you if the command engine is currently processing something, or it’s listening on the command exchange.

network channel

For the sake of simplicity, suppose that we are going to deal with one network client for now.

The wire protocol is going to be UTF-8 JSON delimited by newline character over TCP socket. Here’s the Exec format:

{ "type": "exec", "command_line": "compile" }

An exec describes each round of command execution. When a JSON message is received, it is written into the channel’s own queue.

Here’s the Status event format for now:

{ "type": "status_event", "status": "processing", "command_queue": ["compile", "server"] }

Finally, we will introduce a new Int setting called serverPort that can be used to configure the port number. By default this will be calculated automatically using the hash of the build’s path.

Here’s a common interface for command channels:

abstract class CommandChannel {

private val commandQueue: ConcurrentLinkedQueue[Exec] = new ConcurrentLinkedQueue()

def append(exec: Exec): Boolean =

commandQueue.add(exec)

def poll: Option[Exec] = Option(commandQueue.poll)

def publishStatus(status: CommandStatus, lastSource: Option[CommandSource]): Unit

}

server command

Now that we have a better idea of the command exchange and command channel, we can implement the server as a command.

def server = Command.command(Server, Help.more(Server, ServerDetailed)) { s0 =>

val exchange = State.exchange

val s1 = exchange.run(s0)

exchange.publishStatus(CommandStatus(s0, true), None)

val Exec(source, line) = exchange.blockUntilNextExec

val newState = s1.copy(onFailure = Some(Server),

remainingCommands = line +: Server +: s1.remainingCommands).setInteractive(true)

exchange.publishStatus(CommandStatus(newState, false), Some(source))

if (line.trim.isEmpty) newState

else newState.clearGlobalLog

}

This is more or less the same as what the shell command is doing, except now we are blocking on the command exchange. In the above, exchange.run(s0) starts a background thread to start listening to the TCP socket. When an Exec is available, it prepends the line and "server" command.

One benefit of implementing this as a command is that it would have zero effect on the batch mode running in the CI environment. You run sbt compile, and the sbt server will not start.

Let’s look at this in action. Suppose we have build that looks something like this:

lazy val root = (project in file(".")).

settings(inThisBuild(List(

scalaVersion := "2.11.7"

)),

name := "hello"

)

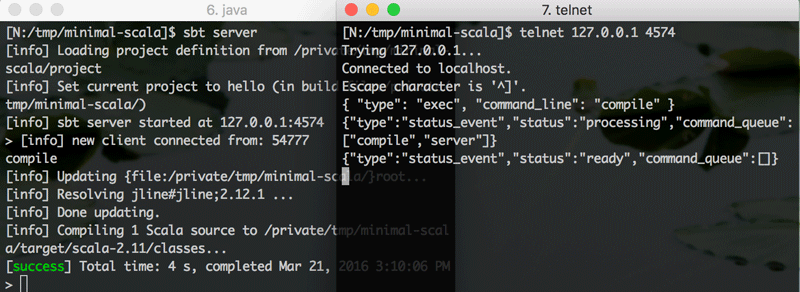

Nativate to the build in your terminal, and run sbt server (using a custom build of 1.0.x):

$ sbt server

[info] Loading project definition from /private/tmp/minimal-scala/project

....

[info] Set current project to hello (in build file:/private/tmp/minimal-scala/)

[info] sbt server started at 127.0.0.1:4574

>

As you can see, the server has started on port 4574, which is unique to the build path. Now open another terminal, and run telnet 127.0.0.1 4574:

$ telnet 127.0.0.1 4574

Trying 127.0.0.1...

Connected to localhost.

Escape character is '^]'.

Type in the Exec JSON as follows with a newline:

{ "type": "exec", "command_line": "compile" }

On the sbt server you should now see:

> compile

[info] Updating {file:/private/tmp/minimal-scala/}root...

[info] Resolving jline#jline;2.12.1 ...

[info] Done updating.

[info] Compiling 1 Scala source to /private/tmp/minimal-scala/target/scala-2.11/classes...

[success] Total time: 4 s, completed Mar 21, 2016 3:00:00 PM

and on the telnet window you should see:

{ "type": "exec", "command_line": "compile" }

{"type":"status_event","status":"processing","command_queue":["compile","server"]}

{"type":"status_event","status":"ready","command_queue":[]}

Here’s a screenshot:

Note that this API is defined in terms of the wire representation, not case classes etc.

IntelliJ plugin

While Johan and I were working on the server side, Martin researched how to make an IntelliJ plugin. Since the plugin is currently hardcoded to hit port 12700, let’s add that to our build:

lazy val root = (project in file(".")).

settings(inThisBuild(List(

scalaVersion := "2.11.7",

serverPort := 12700

)),

name := "hello"

)

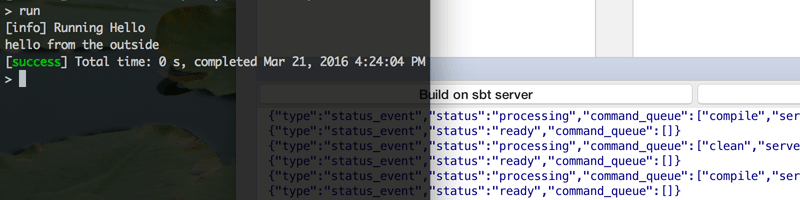

The IntelliJ plugin has three buttons: “Build on sbt server”, “Clean on sbt server”, and “Connect to sbt server”. First run sbt server from the terminal, and then connect to the server. Next, hitting “Build on sbt server” should start compilation.

It worked. Similar to the telnet, the plugin currently just prints out the raw JSON events, but we can imagine this could contain more relevant information such as the compiler warnings.

console channel

Next piece of the puzzle was making a non-blocking readLine. We want to start a thread that listens to the human, but using JLine would making a blocking call that prevents anything else.

I have a solution that seems to work for Mac, but I have not yet tested on Linux or Windows.

I am wrapping new FileInputStream(FileDescriptor.in) with the following:

private[sbt] class InputStreamWrapper(is: InputStream, val poll: Duration) extends FilterInputStream(is) {

@tailrec

final override def read(): Int =

if (is.available() != 0) is.read()

else {

Thread.sleep(poll.toMillis)

read()

}

}

Now when I call readLine from a thread, it will spend most of its time sleeping instead of blocking on the IO. Similar to the shell command, this thread will read a single line and exit. When the console channel receives a status event from the CommandExchange, it will print out the next command. This emulates someone typing in a command and indicates that there has been an exec command from outside.

If this works out, sbt server should function more or less like a normal sbt shell except for an added feature that it will also accept input from the network.

summary and future works

- sbt server can be implemented as a plain command without changing the existing architecture much.

- JSON-based socket API will allow IDEs to drive sbt from the outside safely.

Now that we can change the sbt code, we should allow Exec to have a unique ID that gets included into the associated events. I am thinking of something like the following:

{ "type": "exec", "command_line": "compile", "id": "29bc9b" } // I write this

{"type":"problem_event","message":"not found: value printl","severity":"error","position":{"lineContent":"printl","sourcePath":"\/temp\/minimal-scala","sourceFile":"file:\/temp\/minimal-scala\/Hello.scals","line":2,"offset":2},"exec_id":"29bc9b"}

While command execution needs to be batched to avoid the conflict, we can allow querying of the latest State information such as the current project reference, and setting values. The query-response communication could also go into the socket.

The source is available from: